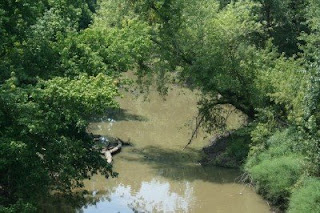

This is a view of the trickling stream that flows from Poison Spring in Arkansas. It can be viewed along the nature trail at Poison Spring State Park.

At the time of the Battle of Poison Spring, the stream or "branch" was flowing with much greater force due to heavy rains that had deluged the area over previous weeks.

As the Union retreat at Poison Spring degenerated into a rout, many of the Federal troops fled the battlefield in any direction possible. It was at this stage of the fighting that alleged murders of Union black soldiers took place.

According to Federal accounts, many men from the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry were shot down by Confederate troops as they were either taken prisoner or tried to flee. The eyewitness accounts are silent as to how many such incidents allegedly took place, but the allegations do surface in a number of the post-battle reports and accounts.

Confederate accounts also indicate that Union black soldiers were killed as they tried to flee the battlefield. Southern eyewitness accounts generally alleged that the men of the 1st and 2nd Choctaw and Chickasaw Regiments were responsible for these actions, noting that the families of these men had suffered greatly at the hands of these same Union troops prior to the beginning of the Red River Campaign.

The latter fact was definitely true. Outrages visited on Choctaw and Chickasaw homes and farms by Union troops had caused a massive flood of refugee men, women and children to flee south from their lands to the areas along the Texas border where they could be protected by Confederate forces. Many of these refugees were family members of Choctaw and Chickasaw soldiers that fought on the Southern side at Poison Spring and there can be little doubt but that they held grudges over the treatment of their loved ones.

Several of the Confederate accounts also note that as the black Union soldiers attempted to flee at the end of the battle, they did not throw down their weapons, but "shuffled" along carrying their firearms with them. This is strangely similar to the accounts of Southern troops describing the alleged massacre at Fort Pillow, Tennessee.

Could there have been something in the pysche of Union black troops that made them unwilling to surrender their weapons? It is certainly possible, considering that for the most part they had been slaves prior to the war and ownership or use of firearms was generally forbidden to them. The possession of a musket or rifle to a black soldier certainly would have been a powerful symbol of his new found freedom and it is reasonable to think that he would have been extremely relunctant to part with it.

It is interesting to contemplate whether the refusal of men from the 1st Kansas Colored to throw down their weapons at Poison Spring might have contributed to alleged post-battle killings there.

It is also worth noting that Colonel James Williams, the commander of Union forces during the battle, reported that nearly half of the men in the regiment had either been killed or wounded during the actual fighting and before the beginning of the retreat. The regiment was stationed in a position where it received massive fire from superior Confederate artillery and the main infantry battle lines of the Southern forces.